Ketten- und Ritzelverschleiß: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

(→Wie die Kette in das Kettenblatt greift: Video eingebunden) |

(→Wie die Kette ins Ritzel greift: Bild hinzugefügt) |

||

| Zeile 57: | Zeile 57: | ||

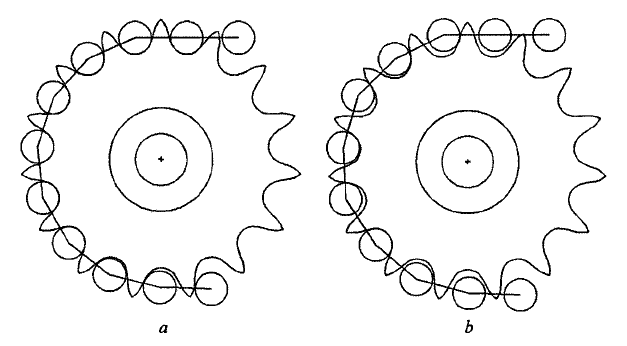

The American Chain Association manual (1972 edition) includes the image below, showing engagement of a new and worn chain with a new sprocket. The worn chain, at the right, is shown with links of unequal length. That actually occurs, because the distance between pins with inner side plates increases due to wear, while that of links with outer side plates -- those which hold the pins -- does not. Uneven roller wear, however, compensates for this in part. Uneven sprocket-tooth wear also does, if the same teeth are always engaged by inner or outer plates. The image at the right is, however, unrealistic in showing chain wear without sprocket wear. It would be unusual to install a worn chain on a new sprocket. The sprocket shown has an odd number of teeth, such that the teeth cannot wear in to accommodate the unequal length of the links. | The American Chain Association manual (1972 edition) includes the image below, showing engagement of a new and worn chain with a new sprocket. The worn chain, at the right, is shown with links of unequal length. That actually occurs, because the distance between pins with inner side plates increases due to wear, while that of links with outer side plates -- those which hold the pins -- does not. Uneven roller wear, however, compensates for this in part. Uneven sprocket-tooth wear also does, if the same teeth are always engaged by inner or outer plates. The image at the right is, however, unrealistic in showing chain wear without sprocket wear. It would be unusual to install a worn chain on a new sprocket. The sprocket shown has an odd number of teeth, such that the teeth cannot wear in to accommodate the unequal length of the links. | ||

[[Datei:Sprockets-aca.png|center|Zeichnung eines Kettenverschleißes]] | |||

Many reference works indicate that tension on the chain decreases in a proportional sequence from one link to the next, back from the pulling run of chain, all the way around to where the chain comes onto the sprocket. That analysis takes no account of the need for the pull on the sprocket to be in the same direction as the chain, or of the different angles at which the chain's rollers bear on the sprocket. | Many reference works indicate that tension on the chain decreases in a proportional sequence from one link to the next, back from the pulling run of chain, all the way around to where the chain comes onto the sprocket. That analysis takes no account of the need for the pull on the sprocket to be in the same direction as the chain, or of the different angles at which the chain's rollers bear on the sprocket. | ||

Version vom 30. Mai 2018, 09:50 Uhr

Fahrradfahrer sprechen oft von Kettenlängung, so als ob die seitlichen Laschen der Kette durch die Kräfte des Pedalierens aus ihrer Form gezogen würden. So funktioniert das natürlich nicht. Der Hauptgrund für Kettenlängung ist der Materialverschleiß der Niete an der Stelle, wo sie sich in der Buchse (oder "Halbbuchse" der buchsenlosen Kette) durch das ständige Strecken und Entspannen der Kette und dem Wechsel von Ritzel zu Ritzel beim Schaltvorgang dreht. Wenn man eine alte und verschlissenen Kette auseinanderbaut, kann man leicht die Einkerbungen durch das Reiben der Buchsen an den Seiten der Niete erkennen. Bei buchsenlosen Ketten hat die Innenkante des Innenlaschenlochs eine geschmeidige Kante statt einer harten Kante. Das trägt vermutlich zur längeren Lebensdauer von buchsenlosen Ketten bei.

Kette und Ritzel in verschiedenen Verschleißzuständen

Auf den folgenden Bildern wird die Kette im Uhrzeigersinn um das Ritzel geführt. Das heißt, dass die Kette auf der rechten Seite abwärts gezogen wird.

Neue Kette auf neuem Ritzel

Wenn eine neue Kette ein neues Ritzel umschlingt, drückt jede Rolle, die auf dem Ritzel aufliegt, mehr oder weniger mit der gleichen Kraft gegen den korrespondierenden Zahn des Ritzels. So verteilt sich die Last und der Druck gleichmäßig über etwa die Hälfte der Ritzelzähne (im Beispielbild oben etwa zehn bis elf Rollen). Die Mitte jeder Rolle ist bis zur Mitte der nächstgelegenen Rolle ziemlich exakt 12,7 mm (1/2 Zoll) entfernt. Dieses Maß nennt man Zahnabstand der Kette. Die Ritzelzähne sind so geformt, dass die Mitte der Biegung, die jedes Tal ausmacht, exakt 12,7 mm (1/2 Zoll) von der nächsten Talmitte entfernt liegt. Der Durchmesser des Ritzels wird berechnet aus dem Zahnabstand und der Zahl der Ritzelzähne.

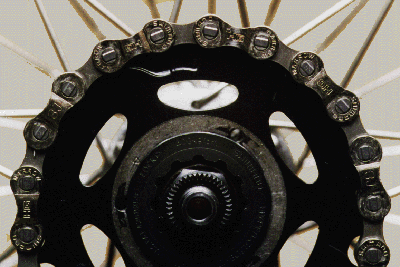

Verschlissene Kette auf verschlissenem Ritzel

Diese Kette und das Ritzel sind gemeinsam verschlissen. Man kann das Licht an einigen Stellen unter der Kette hindurchscheinen sehen. Die verschlissene Kette hat sich "gelängt", so dass sie nicht mehr in den originalen Abstand zwischen den Ritzelzähnen passt. Das Ritzel ist so weit verschlissen, dass die Abstände zwischen den Zähnen der gelängten Kette angepasst sind. Auf dem Bild oben hängt die Kette lose über dem Ritzel. Beim Pedalieren unter Last ist der obere Antriebstrumm unter Spannung und der untere nicht. In dieser Situation bei gemeinsam verschlossenen Komponenten kann es passieren, dass die Kette oben auf den Zähnen aufliegt und herumgeführt wird.

Dieses Bild zeigt zwei Ritzel. Man erkennt ein stark verschlissenes Ritzel im Vordergrund (silbrig) und ein neues direkt dahinter (schwarz) von der rechten Seite aus gesehen. Bei einem neuen Ritzel ist die Zahnflanke, auf die die Rolle drückt, senkrecht zur Zugkraft der Kette ausgerichtet. Die verschlissenen Zähne sind zu Rampen geworden, auf denen die Kette unter Last hinauf rutscht. Die Rollen rutschen so weit hinauf, bis sie den Radius erreicht haben, der dem vergrößerten Abstand von Niete zu Niete entspricht. Der effektive Durchmesser des Ritzels (und damit der effektive Zahnabstand) ist größer geworden, da die Kette nicht länger in den Talsenken aufliegt.

Neue Kette auf verschlissenem Ritzel

Der Hauptteil des Antriebs wird in dieser Kombination auf der linken Seite, wo die Kette sich mit dem Ritzel zuerst verbindet, ausgeführt. Da die Abstände bei Kettenblatt und Kette nicht zusammenpassen, erreichen die Rollen auf der rechten Seite, wo die Kette das Ritzel wieder verlässt, fast nichts, um das Ritzel weiterzutreiben. Stattdessen werden die Rollen durch den vergrößerten Abstand der Ritzelzähne einfach angehoben. Die Last durch das Pedalieren konzentriert sich somit fast ausschließlich auf der linken Seite. Zudem rollt die Rolle den Zahn hinauf, während sie diesem im Laufe einer Umdrehung folgt. Das erzeugt zusätzlichen Verschleiß an Rollen und Buchsen (bzw. Halbbuchsen). Bei einer passenden Kette bewegen sich die Rollen jeweils nur ein kleines Stück, wenn sie sich mit dem Ritzel verbinden und dann wieder beim Lösen vom Ritzel.

Verschlissene Kette auf neuem Ritzel

Wegen der nicht passenden Abstände bei Ritzelzähnen und Kette ist die Last fast ausschließlich auf der rechten Seite konzentriert. Auf der linken Seite besteht kein richtiger Kontakt zwischen Kette und Ritzel. Das neue Ritzel wird schnell verschleißen, um sich dem Zahnabstand der Kette anzupassen.

Bei einem Ritzelpaket werden manche Ritzel häufiger genutzt als andere. Hier läuft die Kette manchmal auf einem fast neuen Ritzel innerhalb des ziemlich alten Ritzelpakets. Daher ist diese Kombination gar nicht so unwahrscheinlich.

Wie die Kette ins Ritzel greift

Now let's look into details of how the chain and sprocket work with each other. For now, let's consider the tension from the pulling run of a chain on a rear sprocket. Let's assume that the chain pulls horizontally from the top of the sprocket.

From the center of each roller of a new chain to the center of the next is precisely 1/2" (12.7 mm). This dimension is known as the "pitch" of the chain. The diameter of the sprocket is determined by the pitch and the number of teeth. The pitch circle (actually, a polygon with sides 1/2" long) is where the rollers sit if they are all at the same distance from the center of the sprocket. The sprocket teeth are made so that the rear face of each one at the pitch circle is 1/2" from the next. Each roller is free to engage and disengage, despite tension, because the next link ahead of the sprocket is pulling in a straight line away from a tooth which is tilted away from it.

The distance between sprocket teeth increases from their bottoms to their tops. The rollers can rise up the backs of the teeth only until the distance between the teeth approaches the pitch of the chain. Even though the profile of the teeth allows them freely to engage and disengage, tension on the chain traps it behind the teeth. The last roller which is about to disengage loses contact with the sprocket tooth while slightly inside the pitch circle. Otherwise, rollers farther back around the sprocket could not be farther inside the pitch circle, as they must be pull less hard -- and they do pull less hard, as we shall see.

The video below gives examples of new and old chains running on new and old sprockets, and informs the discussion which follows.

Due to the slope of the tooth surface, chain tension is pulling the rollers outward, parallel to the tooth surface, as well as forward. Each roller can roll outward on the tooth surface, though with some internal friction. The roller which is about to disengage from the sprocket is held down by the link behind it, and so forth. Force which cannot be taken up by each roller is passed to the next roller, and so on, back around the sprocket -- in tension from each link pin to the previous one. The sum of all the forces which sprocket teeth apply to the rollers must be in the opposite direction from the chain pull, and in line with the chain.

For the force on a new sprocket to be in line with the chain, the first few rollers (fewer with a smaller sprocket) must take most of the load. As mentioned, the first roller pushes the sprocket downward. A few rollers behind the first one, depending on tooth form and sprocket size, may also push the sprocket downward. At some point depending on the tooth form, the changing angle around the sprocket allows rollers to begin pushing upward to cancel the downward push from the first few rollers. Farther back yet, a roller or rollers may be completely disengaged from the backs of the teeth, possibly resting in the valleys between teeth. These rollers can only push inward radially. There is no chain tension at this location beyond what is matched by tension from the return run and/or due to friction. And farther back yet, rollers approaching the return run of chain may be engaging the opposite faces of the teeth, depending on the width of the teeth, tension of the return run and chain wear.

The chain should wrap far enough around the sprocket that the return run of the chain can be nearly slack. Common advice is that a chain should wrap at least 1/3 turn around a sprocket. With typical bicycle chain drive, 1/2 turn is more usual.

With a worn sprocket, as shown in the video, either the chain's wrap around the sprocket, the tension on the return run, or both, must be greater.

The amount of tangential vs. radial force from a roller is very sensitive to where a it sits on the concave, curved surface between the bottom of the valley and the back of the tooth. The chain is constantly finding the position which balances upward and downward forces. With a new chain and sprocket, this balancing act is barely visible, involving radial adjustments of a few hundredths of an inch. Only a very light tension on the return run of chain is necessary to bring it into engagement with the sprocket. This tension is provided by the sprung cage of a rear derailer, or the weight of the return run in a derailerless system. The light tension on the return run subtracts from that of the pulling run and shifts the location where the rollers fall into the gaps away from the return run. The gaps must be deep and wide enough that the links can run free at that location, or the chain will bind. The chain may or may not bear on the front face of the teeth near the return run and pull lightly back on the sprocket.

The American Chain Association manual (1972 edition) includes the image below, showing engagement of a new and worn chain with a new sprocket. The worn chain, at the right, is shown with links of unequal length. That actually occurs, because the distance between pins with inner side plates increases due to wear, while that of links with outer side plates -- those which hold the pins -- does not. Uneven roller wear, however, compensates for this in part. Uneven sprocket-tooth wear also does, if the same teeth are always engaged by inner or outer plates. The image at the right is, however, unrealistic in showing chain wear without sprocket wear. It would be unusual to install a worn chain on a new sprocket. The sprocket shown has an odd number of teeth, such that the teeth cannot wear in to accommodate the unequal length of the links.

Many reference works indicate that tension on the chain decreases in a proportional sequence from one link to the next, back from the pulling run of chain, all the way around to where the chain comes onto the sprocket. That analysis takes no account of the need for the pull on the sprocket to be in the same direction as the chain, or of the different angles at which the chain's rollers bear on the sprocket.

Strain (actual elongation of the chain and compression of the rollers and sprocket teeth under load) slightly lengthens the chain links which are under the most tension, allowing them to migrate slightly farther outward on the sprocket teeth. The tension on the chain varies cyclically during the pedal stroke, and with it, the effect of strain, and of friction. A strobed video might be able to reveal this effect, and a fairly simple analysis could quantify it.

Bei langen Zähnen ist es anders

A sprocket with tall teeth is standard in a derailerless drivetrain, to reduce the risk of the chain's coming off. Sprockets of older (pre-Hyperglide) cassettes and freewheels also had taller teeth than recent models.

If the chain and sprocket are new, they engage and disengage the same as with shorter teeth. The tips of the teeth do not contact the rollers. The tips only guide the side plates to keep the chain on the sprocket.

Wear is very different though if the sprocket has tall teeth. The chain rides up the teeth, but as the chain and sprocket wear together, the backs of the sprocket teeth become hook-shaped rather than only sloped. The profile of the worn teeth is as bold as possible while still allowing the worn chain to disengage freely.

The image below shows a new chain on a worn sprocket with tall teeth. At the blue arrow in the image, you can see how the teeth are hooked. Bad things happen!

New chain old sprocket with tall teeth

The new, unworn chain links fit the bottom of the gaps between sprocket teeth. Chain tension from pedaling pulls the links so the rollers are trapped behind the hooked teeth. As each roller comes around to the top of the sprocket, the hook pulls it downward (red arrow), then chain tension overcomes this pull. The roller breaks loose, rolling up the back of the hook, so the hook yanks the chain backward slightly with relation to the sprocket. Then the roller pops off and the chain jumps slightly forward. This happens for every roller which comes around, dozens of times per second. The resulting roughness can be felt through the pedals. The roughness is worse than with teeth which are only sloped.

One tooth and one roller take all of the drive force as the roller is climbing the tooth, resulting in accelerated chain wear. The roller rolls farther. Power is lost to excess roller motion and to vibration.

Now let's also look at the bottom of the sprocket. Where the chain is about to engage (green arrow), its forward position due to other rollers' being behind the hooks places a roller on top of a tooth. If the tension on the lower run of chain is high enough to force the link into engagement, then additional power is lost as the roller pops onto the tooth, pulling the chain slightly backward. If the lower run is slack, the roller and the others behind it come around to the top sitting on top of the teeth, and then the chain jumps forward by one tooth with a clunk.

A new chain on a hooked sprocket may behave well when the cranks are given a test spin on the workstand, but jump forward under power. This may happen with only some sprockets on a derailer-equipped bicycle, not with others, as they may have unequal wear.

A new chain on a worn sprocket of a derailerless drivetrain, held in place by adjusting the position of the rear wheel, can have little enough slack to force it to engage, but still at a cost in efficiency and chain wear.

A worn sprocket can often be turned over, doubling its wear life. But, avoid this trick if it worsens the chainline, or with the asymmetrical (when new) teeth of sprockets used with derailers, or with a fixed gear, coaster brake or kickback rear hub where the chain pulls from the bottom as well as the top.

If the teeth are tall enough to develop hooks, a hooked sprocket can be refurbished for use with a new chain by grinding the hooks off.

Wie die Kette in das Kettenblatt greift

The chain engages a chainwheel differently from a rear sprocket. Engagement with the chainwheel is with the driving run of chain and disengagement, with the lightly-tensioned return run.

Nonetheless, the basic form of the chain's travel around the chainwheel is the same. There is one notable difference: the chain engages under tension from over the top of hooked teeth -- if they are hooked -- rather than digging in behind them. Jumping forward of the chain with a worn chainwheel occurs at the lightly-tensioned return run rather than the pulling run, and involves less power loss. A bit of jumping forward of a worn chain is visible even in the video below, with a new chainwheel.

Kettenverschleiß bestimmen

Die Standardvorgehensweise, um den Kettenverschleiß zu bestimmen benötigt entweder ein Lineal oder ein Stahlmaßband mit Zolleinteilung. Dazu muss man die Kette nicht vom Fahrrad demontieren. Man platziert die Nullmarkierung des Messinstruments seitlich an einem Niet und zählt genau 12 ganze Kettenglieder (12 * 1 Zoll = 1 Fuß) ab. Bei einer neuen unverschlissenen Kette wird der korrespondierende Niet genau auf der 12 Zoll-Markierung liegen. Bei einer verschlissenen Kette wird er jenseits dieser Markierung liegen.

Um genau messen zu können, benötigt die Kette Spannung. Das geht am besten am Fahrrad montiert oder in der Luft hängend. Auf jeden Fall sollte man ein Metallmessgerät benutzen, weil Holz, Kunststoff oder Gewebe sich in ihrer Länge zu stark verändern können.

Hierdurch erhält man ein direktes Maß des Ketten- und ein indirektes Maß des Ritzelverschleißes.

Zollbasiertes Messen

- Wenn der Niet weniger als 1/16 Zoll jenseits der 12 Zol Markierung liegt, ist alles in Ordnung.

- Wenn der Niet etwa 1/16 Zoll jenseits der 12 Zoll Markierung liegt, solltest Du die Kette wechseln. Die Ritzel sind vermutlich ohne Beschädigung.

- Ist die Markierung 1/8 Zoll entfernt, ist die Kette zu lange gefahren worden, und die Ritzel (oder zumindest das am häufigsten genutzte), sind ordentlich verschlissen. Wenn man an diesem Punkt nur die Kette wechselt (ohne Ritzeltausch), kann es sein, dass die Kette noch gut läuft ohne zu springen. Die verschlissenen Ritzel werden jedoch den Kettenverschleiß deutlich beschleunigen, bis die Kette auf den Ritzelverschleiß angepasst ist.

- Jenseits der 1/8 Zoll Markierung wird eine neue Kette auf jeden Fall auf den Ritzeln springen - insbesondere auf den kleineren Ritzeln.

Metrisches Messen

Falls Du nur metrische Messinstrumente an der Hand hast, zählst Du zehn (25,4 cm) bzw. 15 (38,1 cm) Kettenglieder ab.

- Wenn der Niet weniger als 25,5 cm (oder zwischen 38,2 und 38,3 cm) jenseits liegt, ist alles in Ordnung.

- Wenn der Niet etwas mehr als 25,5 cm liegt (oder sich 38,3 cm annähert), solltest Du die Kette wechseln. Die Ritzel sind vermutlich ohne Beschädigung.

- Ist die Markierung 25,7 cm (oder 38,5 cm) entfernt, ist die Kette zu lange gefahren worden, und die Ritzel (oder zumindest das am häufigsten genutzte), sind ordentlich verschlissen. Wenn man an diesem Punkt nur die Kette wechselt (ohne Ritzeltausch), kann es sein, dass die Kette noch gut läuft ohne zu springen. Die verschlissenen Ritzel werden jedoch den Kettenverschleiß deutlich beschleunigen, bis die Kette auf den Ritzelverschleiß angepasst ist.

- Jenseits der 25,7 cm (oder 38,5 cm) Markierung wird eine neue Kette auf jeden Fall auf den Ritzeln springen - insbesondere auf den kleineren Ritzeln.

Kettenverschleißlehren

Es existieren spezielle Werkzeuge, um den Kettenverschleiß zu messen. Dies sind etwas weniger aufwändig, jedoch in keinem Fall notwendig. Zudem sind sie mit Ausnahme der beiden Werkzeuge von Shimano (TL-CN40 und TL-CN41) ungenau, weil der Bewegungsspielraum der Rollen den Verschleiß der Nieten in der Messung verfälscht.

Kettenlänge

Dieser Aspekt wird ausführlich im Artikel über Einstellen der Schaltung erläutert.

Siehe auch

- Kettenpflege

- Wenn die Kette abspringt oder klemmt

- Verlängern der Lebensdauer von Kette und Ritzel für Fahrer von Singlespeed- oder Nabenschaltungsfahrrädern.

- sehr schöner Artikel auf Fahrradmonteur.de von Ralf Roletschek

Quelle

Dieser Artikel basiert auf dem Artikel Chain and Sprocket Wear von der Website Sheldon Browns. Originalautor des Artikels ist Sheldon Brown.

- Sattelstützenmaße

- Knarzen, Knacken und Quietschen

- Ritzelabstände (Tabelle)

- Auswechselbarkeit von Vierkant-Kurbelaufnahmesystemen bei Innenlagern

- Kettenlinienstandards (Tabelle)

- Ein bequemer Sattel

- Nabenbreiten (Tabelle)

- Alles über Nabenschaltungen

- Shimano Nexus und Alfine Acht-Gang-Naben

- Reifengrößen